Hibbert of Bilton Grange: Rugby town and transatlantic slavery

Dr Katie Donington (Open University)

Introduction

This blog post explores some of the ways that the history and legacies of transatlantic slavery have shaped contemporary society. Using the local history of Rugby town and its environs, it will explore how those stories connect the area to the Atlantic world which an involvement with slavery created. Local history is a valuable way of engaging people with the slaving past. Examining different histories allows us to see familiar locations with new eyes. The past has sometimes been described as a ‘foreign country’, but it can become knowable when we put it in the context of the streets we walk down or the buildings we inhabit.

We saw how impactful local connections to slavery can be during the summer of 2020 when we witnessed an intense scrutiny of Britain’s history of slavery brought about by the Black Lives Matter protests sparked by the murder of George Floyd. Perhaps the most iconic moment of the protests in Britain occurred in Bristol with the toppling of the statue of the slave-trader Edward Colston. Celebrated for his philanthropy with a variety of buildings, street names, and memorials, the representation of Colston as the ‘patron saint of Bristol’ has long displaced the memory of him as a prolific slave-trader. In the wake of Colston falling, local councils, museums and heritage sites have been reckoning with the symbols of slavery which continue to shape the physical landscape.

The toppled statue of Colston at the M Shed museum in Bristol. Image credit: Wikimedia.

The existence of these public markers of the slaving past raise uncomfortable questions for contemporary society regarding the ways in which slavery benefited different local communities – and indeed the nation as a whole – both then and now. Long before protestors took to streets, the work of researching Britain’s history and legacies of slavery has been ongoing in our universities, museums and within communities.

In 2007, during the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade, local organisations were given funding to unearth previously unrecognised histories, which resulted in a flurry of exhibitions, pamphlets, archive guides and walking tours. Some of this material has been digitised by the Remembering 1807 project run by the University of Hull. This example comes from the Warwickshire Record Office who searched their collections to put together an exhibition which included material on local families involved with slave trading, plantation ownership, the naval defence of the slave colonies, Quaker abolitionists and enslaved people.

In 2013, the Legacies of British Slave-ownership project at University College London published their research via an open access online database which used archival documents detailing who received slavery compensation money when the system was abolished in 1833. Using the search function to look for people whose biographical entries includes a reference to ‘Warwickshire’ brings up 63 individuals who were resident in the county, as well as people who were born, baptised, married, educated or died in the area.

We can then dig a little bit deeper and concentrate on the Rugby area; a search in the database for ‘Rugby’ returns 14 individuals associated with the area. There is also a search function to find out where the slave-owners in the database were educated. The return for Rugby School is 7 people.

The research is not comprehensive – there will be people connected to slavery who are not identified through the compensation records because they had already removed themselves from the system in an earlier period, or because they were connected in a different way, for example, as slave traders or West India merchants.

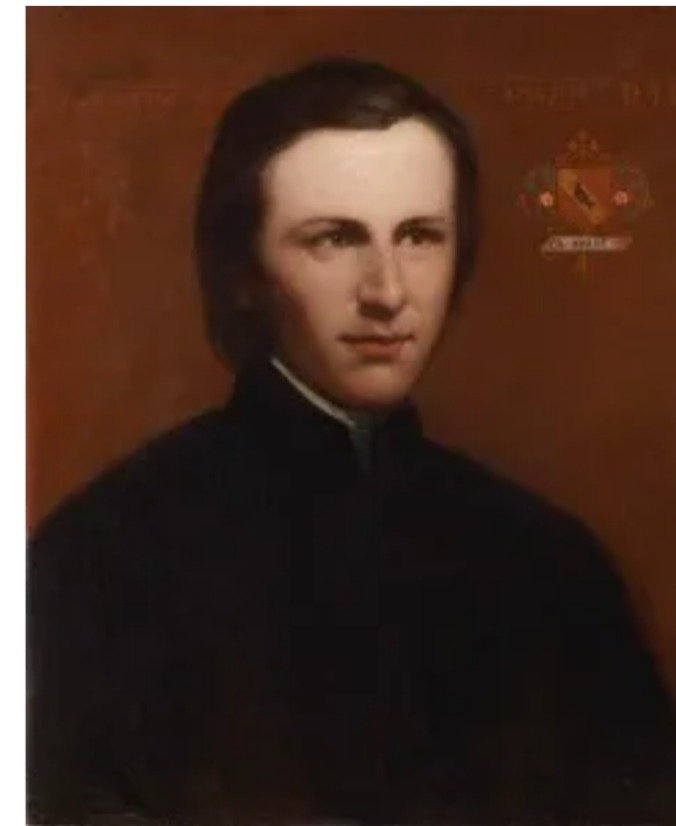

Captain John Hubert Washington Hibbert in Vanity Fair, 28 June 1873. Image credit: Wikidata.

One of the individuals named in the database is Captain John Hubert Washington Hibbert (1804–75) of Bilton Grange – the rather distinguished looking person depicted in an image in Vanity Fair magazine in 1873.

Despite all the fashionable trappings of the Victorian English gentleman, John Washington started off life in rather different circumstances. He was born in Jamaica in 1804, three years before the slave trade was abolished and thirty years before slavery ended. His father was Thomas Hibbert (1761–1807), who like him had been born in Jamaica in 1761. John Washington’s father died in 1807 when he was just three years old. At this point John Washington and his two older brothers Thomas (1795–1845) and Julian (1800–34) inherited their father’s property and fortune which was kept in trust for them until they reached adulthood. The property included the Agualta Vale and Orange Hill plantations located in St Mary’s parish on the north-east side of the island. Alongside this they became the effective owners of an enslaved population of around 800 men, women and children. The Hibbert family had been involved in different aspects of the business of slavery in Jamaica for four generations and had amassed a fortune from it. To understand how John Washington ended up in the records of the slavery compensation commission we have to go back through time to unpick his family’s long-term participation in the system.

The Hibberts and slavery

The Hibberts were part of the dissenting merchant classes of northern England. Their rise up the social ladder started with their initial involvement in the cloth industry in Manchester. The growing importance of Manchester during the eighteenth century stemmed from the expansion of empire and the rise of slavery, which secured the area’s role in the cotton economy. Raw cotton produced by enslaved workers in both the Americas and the Caribbean was shipped to the port at Liverpool for processing in Lancashire. Finished cotton pieces were then sent back to Liverpool for use as barter goods in the slave trade on the coast of West Africa.

In the early eighteenth-century John Washington’s great-great-grandfather was described as a linen draper, and it was this initial involvement with the cloth trade that led to an expansion of their family business into Atlantic commerce. By the mid-eighteenth century his great-grandfather was an established manufacturer of cloth for use in the slave trade. It was from these beginnings in north-west England that the Hibberts developed a commercial empire which spanned from Manchester to Jamaica and eventually the centre of the imperial world: London.

In 1734 John Washington’s great-uncle Thomas Hibbert senior (1710–80) left Manchester for Jamaica. He arrived in Kingston – a bustling mercantile centre of the British Atlantic world. The early years of Thomas senior’s career in Jamaica are unclear, however, there is a reference in the papers of one of the family’s clients – the plantation owner Simon Taylor (1739–1813). Thomas senior, wrote Taylor in 1800, ‘was sent to this country to collect some debts and got acquainted with a Guinea factor who took him into partnership and by the sale of negroes alone made his fortune.’

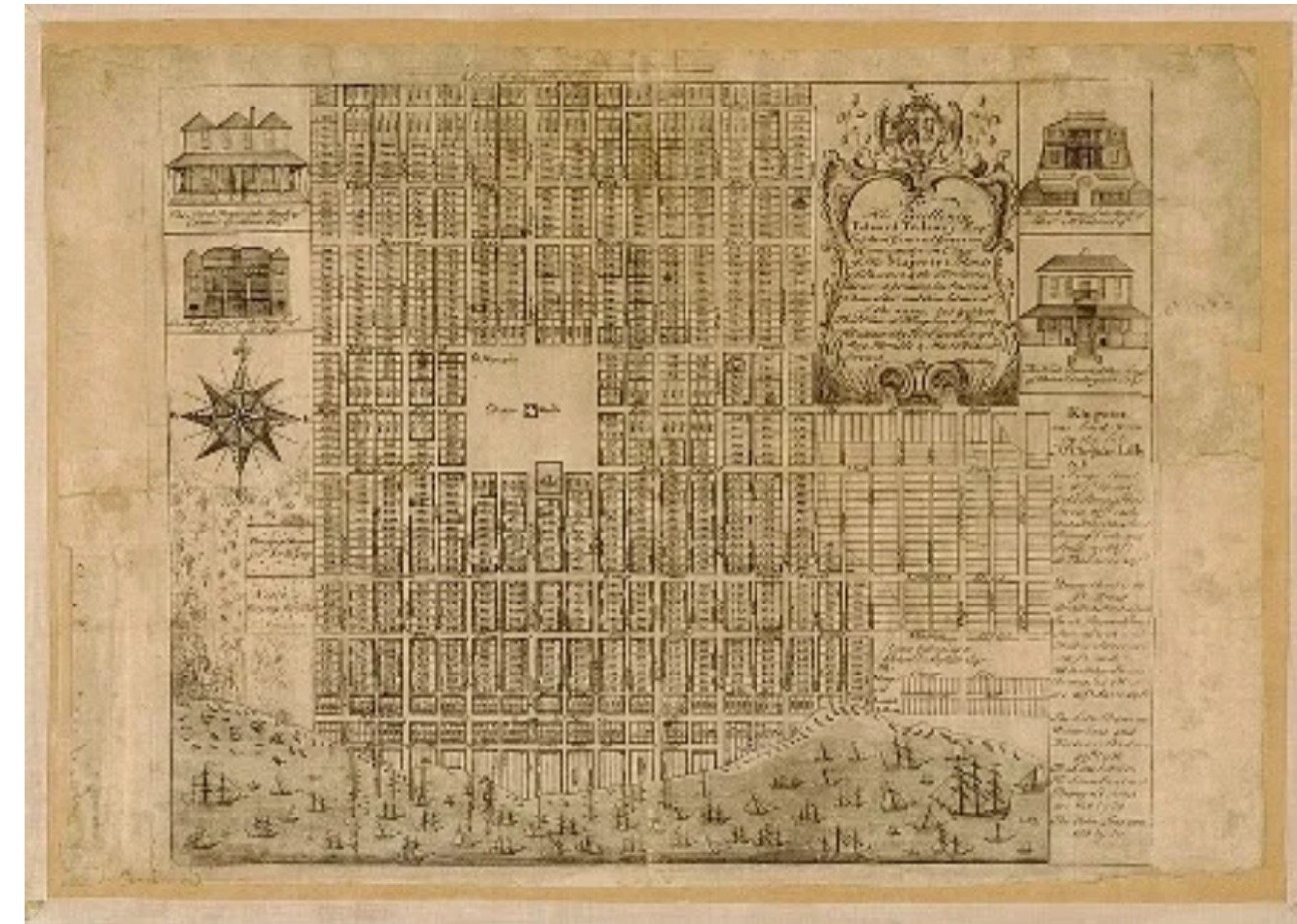

Map of Kingston, Michael Hay, 1740. Image credit: Wikimedia.

By the 1750s Thomas senior had acquired property close to the waterfront in Kingston on Orange Street, an area identified as housing British America’s most densely populated slave yards. Slave yards were spaces used by slave factors – people who bought and sold enslaved people in the Caribbean – to keep enslaved people once they had been taken off the ships but before they were sold on to their clients. According to the Poll Tax list for 1745, there were 1,011 enslaved people being kept on Orange Street.

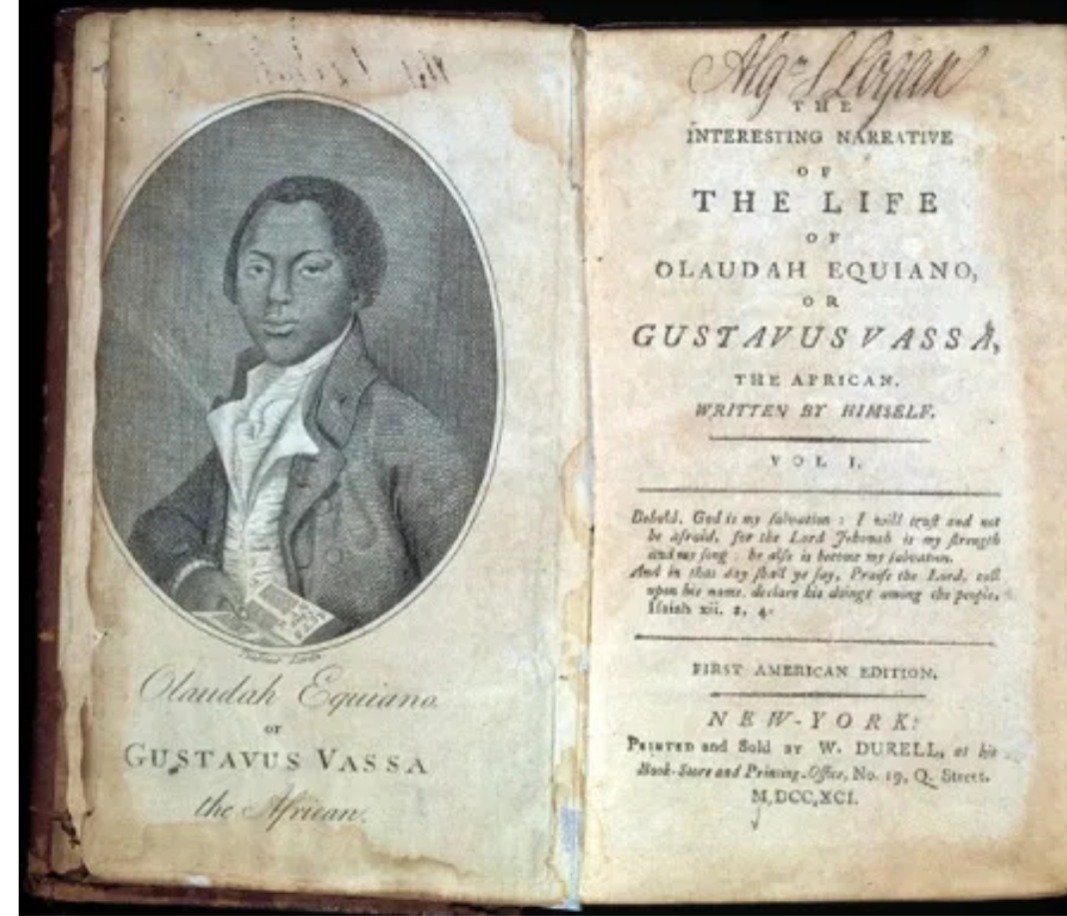

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, 1791. Image credit: Wikimedia.

We can only imagine how grim life must have been trapped in those horribly confined quarters, not knowing what would happen next. An account written by an enslaved man who went on to purchase his own freedom, the abolitionist campaigner Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745–97), gives us a brief glimpse of the conditions. He wrote that: ‘We were conducted immediately to the merchant’s yard, where we were all pent up together like so many sheep in a fold, without regard to sex or age.’ After a period of time the sale of the enslaved began. Equiano wrote of his fear and sorrow at being torn away from the people he had come to know during the journey from Africa:

‘On a signal given, (as the beat of a drum), buyers rush at once into the yard where the slaves are confined, and make a choice of that parcel they like best. The noise and clamor with which this is attended, and the eagerness visible in the countenances of the buyers, serve not a little to increase the apprehension of terrified Africans … In this manner, without scruple, are relations and friends separated, most of them never to see each other again. I remember in the vessel in which I was brought over … there were several brothers who, in the sale, were sold in different lots; and it was very moving on this occasion, to see and hear their cries in parting.’

For the Hibberts this scene was a familiar one and indeed one which was integral to the running of their business. Thomas senior’s nephew, who had travelled from Manchester to join the business in 1766, described similar scenes on board a slave ship where a sale was taking place. He wrote: ‘[I] really expected one half of the white people on board would have been trod to Death by the other half.’

The scale of the Hibberts’s slave trading business was vast. Between 1764 and 1774 they acted as factor for 61 ships, selling 16,254 enslaved people. To put that in context – the population of Rugby today is around 75,000 so that figure would represent around 20% of the inhabitants. And that number related to only ten years of trade for the Hibberts.

In the 1750s Thomas senior’s commercial success afforded him the social status to seek political power. He served as Speaker for the Jamaica House of Assembly and when the capital was briefly moved from Spanish Town to Kingston, the Assembly sat in his grand new home. In order to complete the transformation into the highest ranks of plantation society, Thomas senior purchased a 3000-acre plantation, Agualta Vale in St Mary’s, in 1760.

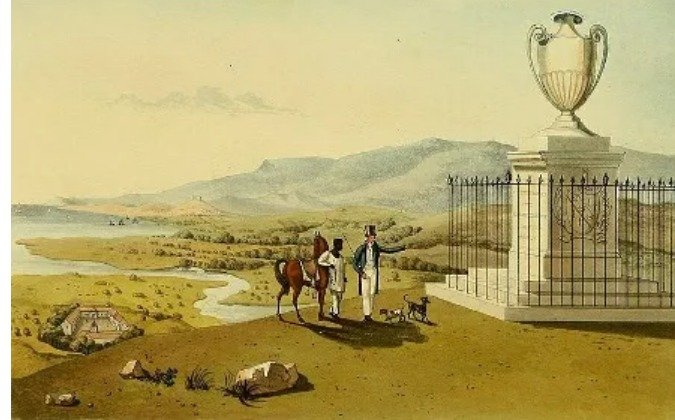

The Hibbert family plantation Agualta Vale, St Mary, Jamaica by James Hakewill. Image credit: Wikimedia.

This image of the estate was created by the artist James Hakewill (1778–1843) in the 1820s and came from a series which was commissioned by the wealthy planters. It is a highly romanticised image which was designed to promote the idea of slavery as a civilised institution – it was a piece of pro-slavery propaganda.

Over the years, Thomas senior invited his brothers and nephews to join the family business in Jamaica. In 1754, John Washington’s grandfather John senior (1732–69) arrived from Manchester. As the Hibberts settled into Jamaican society they bought a further nine estates. By the time slavery ended they also held financial or managerial interests in nineteen more properties. When Thomas senior died in 1780, he left Agualta Vale to his three nephews, alongside an estimated £250,000 which he had accrued from selling enslaved people and money lending.

Two of his nephews were the sons of his brother Robert (1717–84) and had been sent over from Manchester. The third, another Thomas, was the Jamaica-born eldest son of John senior. This was John Washington’s father. By 1796 Thomas had become the sole owner of the plantation plus two neighbouring estates, having bought out his cousins.

So what were conditions like for enslaved people on Agualta Vale? There are very few records which shed light on the experiences of the enslaved on the Hibberts’ plantations and none at all which were created by enslaved people themselves. Between 1817 and 1832 the British government kept a record of how many enslaved people were living in the Caribbean colonies. They took a register every three years and this created some of the most comprehensive documentation we have of enslaved people. From these documents we know that in 1817 there were 817 enslaved people living on the three plantations which made up the Agualta Vale complex. The records tell us the names that the Hibberts had given them, whether or not they were born in Jamaica or Africa, and the racial categorisation that they had been assigned because of their parentage. Some people had the names of their mothers included in the ‘remarks’ section.

We can find out a little bit more about individuals by looking for clues in the archives of the Hibberts themselves. Thomas senior’s nephew Robert junior (1750–1835) arrived in Jamaica in 1771 and he kept a diary which recorded his daily activities. On occasion he mentioned enslaved individuals by name; his manservant London was referenced the most frequently. In 1772 Robert junior noted a few days before Christmas: ‘London flogged for stealing Collard’s wine.’ He recorded when Little Monday was bitten by a mad dog and subsequently died. He also wrote in a displeasured tone when Pope, described as a ‘new Negro’, lost his eye after being sent to the workhouse.

We know from records compiled to document enslaved people who ran away from their owners that eight enslaved people belonging to the Hibberts ended up in the gaols and workhouses in Jamaica having been captured. This isn’t very many, but we shouldn’t read this as an indication that conditions were good for the enslaved people – it was incredibly hard to escape and the punishments for doing so were very harsh. Evidence from the slave court records show us how discipline was maintained on the plantation. In 1822 an enslaved man named Raynes ran away from Great Valley plantation which was owned by the diarist Robert junior. His punishment for was to be transported off the island meaning he would never see his friends and family again. For their loss of property, the Hibberts were paid £40 which has a purchasing power in today’s money of around £2300.

Adolphe Duperly, Destruction of the Roehampton Estate January 1832 (1833). Image credit: Wikimedia.

In 1831 there was an enormous uprising in western Jamaica by around 60,000 enslaved people. Several of the Hibberts’s plantations were affected and Great Valley was burned down. A number of enslaved men and women owned by the Hibberts were captured by the authorities and accused of taking part – their punishments included execution, transportation, flogging and imprisonment in the workhouse.

So what did all this human misery amount to? Put in bald monetary terms, what kind of profits were the Hibberts making from their involvement with slavery? We don’t have a full account of their business records to be able to work out exactly how much money was being generated across their commercial interests in different aspects of slavery. One way to understand how much the family profited is to look at their wills to see how much capital, land and other forms of property they were able to leave to the next generation. Let us focus here on John Washington’s father Thomas, who died in 1807. In his will, his wife Dorothy was entitled to £1000 every year plus a lump sum payment of £1,000. Dorothy was still alive in 1845 so she must have received at least £39,000. His daughter Sacharissa was to be given £10,000 when she turned twenty-one. His three sons Thomas, Julian and John Washington received £10,000 each on reaching twenty-one, a further £10,000 on reaching twenty-five. Further to this Thomas set aside £40,000 to be invested in establishing a country house estate in England. There were other financial commitments to various family members, but these sums represent the biggest claims on his estate. In total they amounted to £149,000 which would have a purchasing value today of around £6.93 million.

The three plantations and the enslaved people on them were to be inherited by Thomas as the eldest son and entailed to his future sons. If Thomas did not have sons then the property would go to Julian and his sons. Finally, if Julian were childless then John Washington and his sons would become the heirs.

Heirs to a slavery fortune

The vast profits generated through their father’s involvement with slavery guaranteed his children a good position in society. Both John Washington and his brother Julian were educated at Eton, with John Washington starting aged fourteen in 1817. Thomas was sent to a Reverend Smith of Winchester and later followed his teacher to Glasgow.

While Julian went on to study at Trinity College, Cambridge, John Washington joined a cavalry regiment of the British Army. Starting off as a Cornet in the First Royal Dragoons, by 1826, aged twenty-two, he had purchased the position of Lieutenant. In 1830 he rose to the rank of Captain, again through purchase. By 1837 John Washington had transferred to the 36th Regiment of Foot. This unit saw active service in Barbados, Canada and Ireland during the period John Washington was serving in it.

John Washington’s brothers experienced very different trajectories. After leaving Cambridge, Julian became involved in radical politics in London. He was a supporter of the free press and served as an editor of the Poor Man’s Guardian. He bought his own printing press which specialised in radical literature. During the early 1830s he financially supported those who had been imprisoned for publishing material deemed illegal by the government. Julian was involved in the establishment of the National Union of the Working Classes and the transformation of the Blackfriars Rotunda into a meeting place for London’s radicals.

Theophila Carlile Campbell (1837–1913) wrote a history of the struggle for press freedoms in which she dedicated several passages to Julian’s role. Her writing indicated a rupture with the Hibbert family. According to her, Julian had ‘separated himself from his family at an early age, and never spoke of them or of his birth to anyone, as far we know. His family affairs were a secret to his most intimate friends.’ Theophila recorded that: ‘there was no doubt that he came of some fine family’, though she added ‘of that or of any other part of his past, or youth, he never spoke’. Julian died in his early thirties in 1834.

Whilst Julian embraced radicalism and John Washington joined the army, their older brother Thomas spent the 1820s embroiled in legal proceedings to determine his mental state. In 1813 he was a student at Cambridge and was there at the same time as his cousin Nathaniel (1794–1865) who remembered that the students referred to Thomas as ‘fool Hibbert’. Throughout his young adult life Thomas had shown signs of mental health problems. His behaviour became increasingly erratic and on several occasions he attacked his mother and sister in their home. As the eldest son Thomas had inherited all his father’s property in land and enslaved people in Jamaica. Therefore it was important for the trustees of his father’s will to establish whether Thomas was of sound enough mind to make decisions about the running of the plantations. In 1821 the court declared Thomas a ‘lunatic’ incapable of managing his person or his estate and he was placed under the guardianship of his uncle John.

Whilst Thomas, Julian and John Washington ploughed their separate paths in the 1820s, the struggle over slavery reignited with the establishment of the Antislavery Society in 1823.

The Hibberts and compensation

The Hibberts were hugely invested in the system of slavery and they had much to lose from the threat of abolition. It is no surprise then that the family were at the forefront of efforts to resist the antislavery movement.

The family had formed a power base in London in 1770 when they had opened a branch house of their Jamaica business there. It focused on lending money to planters in Jamaica and selling the sugar and rum that enslaved people produced. By the early nineteenth century it had become known as ‘the first house in the Jamaica trade’. The key figure in the London merchant house was George Hibbert (1757–1837) – John Washington’s father’s cousin. He was the Chairman of the Society of West India Merchants – a powerful lobbying group who had the ear of the British government. He also served as a Member of Parliament.

George Hibbert, by Thomas Lawrence, 1811. Image credit: Wikimedia.

Photograph of Bilton Grange, Warwickshire, in 1898. Image credit: Wikimedia.

Since 1790 he had been campaigning for those involved in the business of slavery to receive compensation if the government were to end it. His argument was that if Parliament intended to interfere with people’s property – which was legally what enslaved people were defined as – then the owners of that property should receive compensation for its loss. As an anonymous opponent of compensation wrote: ‘Admit the slave-holders claims to compensation, and you admit the justice of slavery.’ Yet this was precisely what occurred in 1833 when the Slavery Abolition Act was passed. Just as George had wanted, as part of the measures taken to bring about emancipation in the Caribbean, Mauritius and the Cape of Good Hope, the slave owners were awarded £20 million in compensation. This created a bureaucratic record of who the slave-owners were at the ending of slavery as 46,000 claimants came forward to try and secure their share of the compensation money.

Given the scale of the Hibberts’ involvement with all aspects of the slavery system it is unsurprising that George lobbied so hard for the payment of compensation. Collectively the family received over £103,000 – a sum that has a purchasing power of £6.2 million in today’s money. In 1835, along with his older brother Thomas, John Washington was awarded £14,337 for 799 enslaved people who were living on the three plantations that his father had established. That sum would be worth around £886,000 relative to its purchasing power now.

Bilton Grange, Rugby town and the legacies of slavery

Four years later, in 1839, John Washington married Julia Talbot née Tichborne (1810–92), the third daughter of Sir Henry Joseph Tichborne. The same year he rented Bilton Grange in Warwickshire, where he resided with his wife, his mother Dorothy and his mentally ill older brother Thomas. Thomas remained living with the family until his death in 1845. At this point with both his older brothers dead having had no children, John Washington became heir to his father’s entire estate.

In 1846, John Washington purchased Bilton Grange from Abraham Hume. He remodelled the house, employing the Gothic architect Augustus W. Pugin (1812–52) to design both the exteriors and interiors. John Washington’s decision to hire Pugin may have been a result of his wife’s connection to the Talbot family, into which she had previously married.

The architect, Augustus Pugin. Image credit: Wikimedia.

John Talbot, the sixteenth Earl of Shrewsbury, was one of Pugin’s most important patrons. Both Julia and the Talbot family were Catholic and John Washington converted in 1846. Given the relationship between Pugin, the Gothic architectural style and the Catholic revival which told place in the mid-nineteenth century, it is possible that this impacted on the choice of architect.

The work took ten years to complete and has been described as ‘one of the … great domestic schemes of Pugin’s mature years’. Relations between architect and patron were strained, with ‘frequent disputes’ breaking out. Details of the renovations carried out at Bilton Grange offer a glimpse into the craftsmanship and design:

‘Pugin greatly expanded a small eighteenth-century house, adding a new wing that completely dominated the existing structure, and creating a sequence of new rooms which included a galleried Great Hall with stained-glass windows. There was a dramatic staircase with carved newel posts in the form of heraldic beasts and birds, some fine carved stone fireplaces with heraldic andirons or firedogs, a rich array of carved and painted panelling, elaborate chandeliers, and decorative metalwork including some finely wrought keys, a Pugin speciality. A range of specially designed tiles and wallpapers featured the Hibbert initials and coat of arms. In its diversity, Bilton Grange represented a typically extravagant and completely coordinated Pugin interior, in his modern medieval style.’ (Atterbury, 1996: p. 194)

As an indication of the cost, the interior design alone was billed at £1,300 which in today’s money would have the purchasing power of around £104,000.

In 1866 the Hibberts sold Bilton Grange and moved to London where they had a property on Hill Street, Berkeley Square. They had transformed the house and surrounding buildings, earning the estate a Grade II listing. In 1887 Bilton Grange became an educational institution and it continues today as an independent preparatory school.

John Washington’s impact on the local area extended beyond his transformation of Bilton Grange. The provision of spiritual sustenance was a common expression of philanthropy for the landed classes and St Marie’s Catholic Church in Rugby owes its existence to John Washington.

Initially the family invited local worshippers to attend a chapel at their home. It soon became clear that the needs of the Catholic community outweighed this provision, so John Washington purchased land on Dunchurch Road and commissioned Augustus W. Pugin to design a church. When the congregation required an extension, he raised the funds for Pugin’s son Edward Welby Pugin to undertake the work.

St Marie’s Catholic Church, Rugby. Image credit: Wikimedia.

In recognition of the part the Hibberts played in the founding of the church the old chancel became known as the Hibbert chapel. The Hibbert coat of arms can be seen entwined with that of his wife Julia in tiling in the church.

Having built the church, John Washington requested that the Rosiminians, otherwise known as the Institute of Charity, would run it. His request was granted and two priests and four lay brothers arrived in 1849.

In later years John Washington acquired further land with the intention of setting up a college and novitiate for the order. He also founded Catholic schools for both boys and girls, as well as a convent with four Sisters of Providence.

Despite having moved to London in 1866, the family’s connections to the church remained strong. In 1872 John Washington paid for a 200-foot tower and spire designed in the Gothic style by Bernard Wheelan. He also ordered eight bells from the Whitechapel Foundry, which are still rung today. On their deaths, John Washington and Julia were interred in the family vault beneath the Hibbert chapel. The church has been designated a Grade II listed building by Historic England.

After slavery

In the last section of this blog post, we’re going to return to Jamaica to consider what happened after slavery ended. The Hibberts’ connection to the island didn’t end when slavery was abolished. They remained as plantation owners, and they also continued with their mercantile business selling the commodities produced by the newly emancipated workforce until the 1860s.

Conditions for those that had been freed from slavery changed very little in the immediate aftermath as there followed a period of what was known as apprenticeship. This system, which lasted between 1834 and 1838, was another form of unfree labour imposed on formerly enslaved people as part of the Abolition Act of 1833. Apprentices had to work for their former owners for 45 hours per week for free. Failure to comply with this resulted in people being sentenced to hard labour in the workhouses.

‘A Jamaica house of correction’, 1837. Image credit: Wikimedia.

When apprenticeship was brought to an end early as a result of increasing unrest among the black population, conditions of work remained incredibly difficult. The power of the white planters was untouched by the abolition legislation – there was no redistribution of land and political and legal power was almost entirely in the hands of the former slave-owners. This created an intensely unequal situation which came to a head in 1865 when a black man was put on trial for trespassing on an abandoned sugar estate in Morant Bay. Many felt that this case symbolised the unfairness of the system which excluded black people from farming their own land and becoming independent.

People marched to the courthouse to protest, led by a black preacher named Paul Bogle. The militia opened fired and 25 people were killed. In the days that followed the rebels seized control in the area and drove out some of the white families that were living there. In response the Governor of Jamaica Edward Eyre (1815–1901) authorised brutal retaliations which resulted in the killing of 439 black people and the flogging and imprisonment of over 600 more. The severity of the reprisals drew the attention of people in Britain and some called for Governor Eyre to be tried for murder. The case became a cause célèbre with some of the best known figures in the nineteenth century lining up to take sides in the debate. For example, Charles Dickens (1812–70) supported Governor Eyre and Charles Darwin (1809–82) thought he should be put on prosecuted. Supporters of Eyre banded together to form the Governor Eyre Defence Committee. If we examined the list of committee members published in The Times then eight names down who do we find? John Washington Hibbert. His name appears close to the top of the list indicating that he would have likely given one of the more substantial donations and taken an active role in organising.

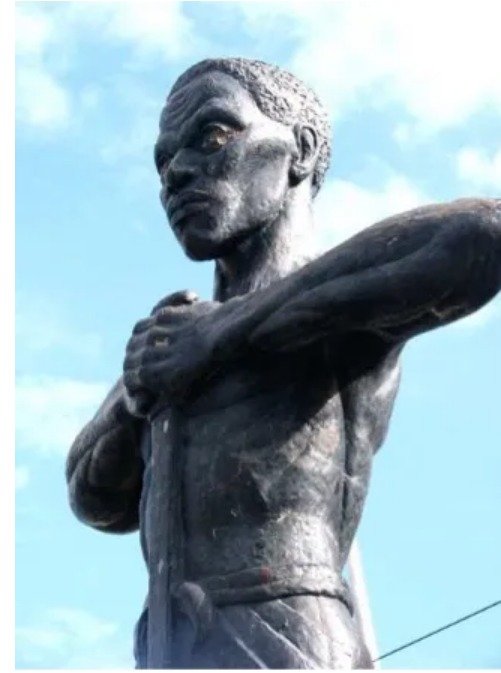

A modern statue commemorating Paul Bogle, who led the Morant Bay rebellion. Image credit: Wikimedia.

So why does this matter? Thirty years after the ending of slavery John Washington was still committed enough to the cause of maintaining white power on the island to lend his support to defending its continuation. He still believed that the use of violence and terror was acceptable to keep the black population under control. This says something very powerful about the way that he viewed the lives of black people in Jamaica.

As the sugar economy in Jamaica went into terminal decline, Agualta Vale was neglected and the great house fell into ruins, the property was eventually revived after it was sold to the Scottish physician Sir John Pringle in 1914 who built a family home on the site. During World War II, it was used as a barrack for the Canadian army. It was later acquired by Sir Harold Mitchell and then eventually it was bought by the Jamaica Producers Group. They had used some sections as offices but the house was destroyed by fire in 1980 and has never been restored. Today the land is used as a banana plantation.

For Britain and the Caribbean, the legacies of slavery still continue to shape the present raising difficult questions about how we address these histories. These are unresolved issues, but in opening up an honest conversation about the slaving past we can begin to understand better how we might work towards a more equitable future.

Citation

Paul Atterbury, ‘Pugin and interior design’, in Atterbury (ed.), A. W. N. Pugin: Master of Gothic Revival (New Haven, CT, 1996), pp. 177–200.

Governor Eyre, c. 1860. Image credit: Wikimedia