Lily Tekseng (University of Cambridge)

Writing empire: spaces imagined and made “real”?

Aside from the focus on athleticism, curricular and pedagogical training, students in public schools also lived, breathed, and produced and reproduced a particular brand of school culture. If the public school was a factory/laboratory, its distinctive culture was the air bracketed within its walls, at once both permeable and permeating.

The vibrant print culture at Rugby in the 18th and 19th century mirrored the boisterous and combative public sphere created by the rise of print media in the 18th and 19th century Britain.

Of the dozen or so student magazines published at Rugby from the 1840s onwards to 1910, almost all of them carried editorials and letters to editors which reflected a lively environment of self-reflexive arguments and criticism. It seems as if each of these magazines had something nasty and funny to say about the other contemporaneous magazines, and all of these, across time, seems to have unanimously hated the school’s official record, The Meteor.

This print media-led student culture in public schools is explored in Talbot Baines Reed’s best known “School stories”, The Fifth Form at St. Dominic’s (1881). Written originally for the Boy’s Own Paper—which was a magazine for adolescents published by the Religious Tract Society with the objective of instilling Christian values in young boys—it explores the rivalry between the Fifth and the Sixth forms in a public school setting, wherein the Fifth form decides to start a new school magazine because the Sixth Form Magazine is “rubbish, and unreadable; and though they condescend to let us see it, I don’t suppose two fellows in the Form ever wade through it.”

Baines Reed was a frequent contributor for the Boy’s Own Paper or BOP, as it was popularly known. BOP carried articles ranging from adventure stories, school stories, articles related to sports, travel, tips on scouting, and so on.

The Boy's Own Paper, front page, 11 April 1891. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

What strikes me in my preliminary survey of these magazines and texts produced for juvenile audience in the Victorian era is how adventure becomes an almost irreplaceable and intrinsic component of these writings.

To a certain extent, the thirst for thrill and adventure, which in turn is the catalyst for conflict and its subsequent resolution, is innate to the construction of a story. It is in the very DNA of a story; it is the key mechanism that carries a narrative.

But I think something interesting happens to the genre of adventure fiction and adventure writing during this period, and strikingly, it corresponds and correlates to the rise and expiration of the British empire.

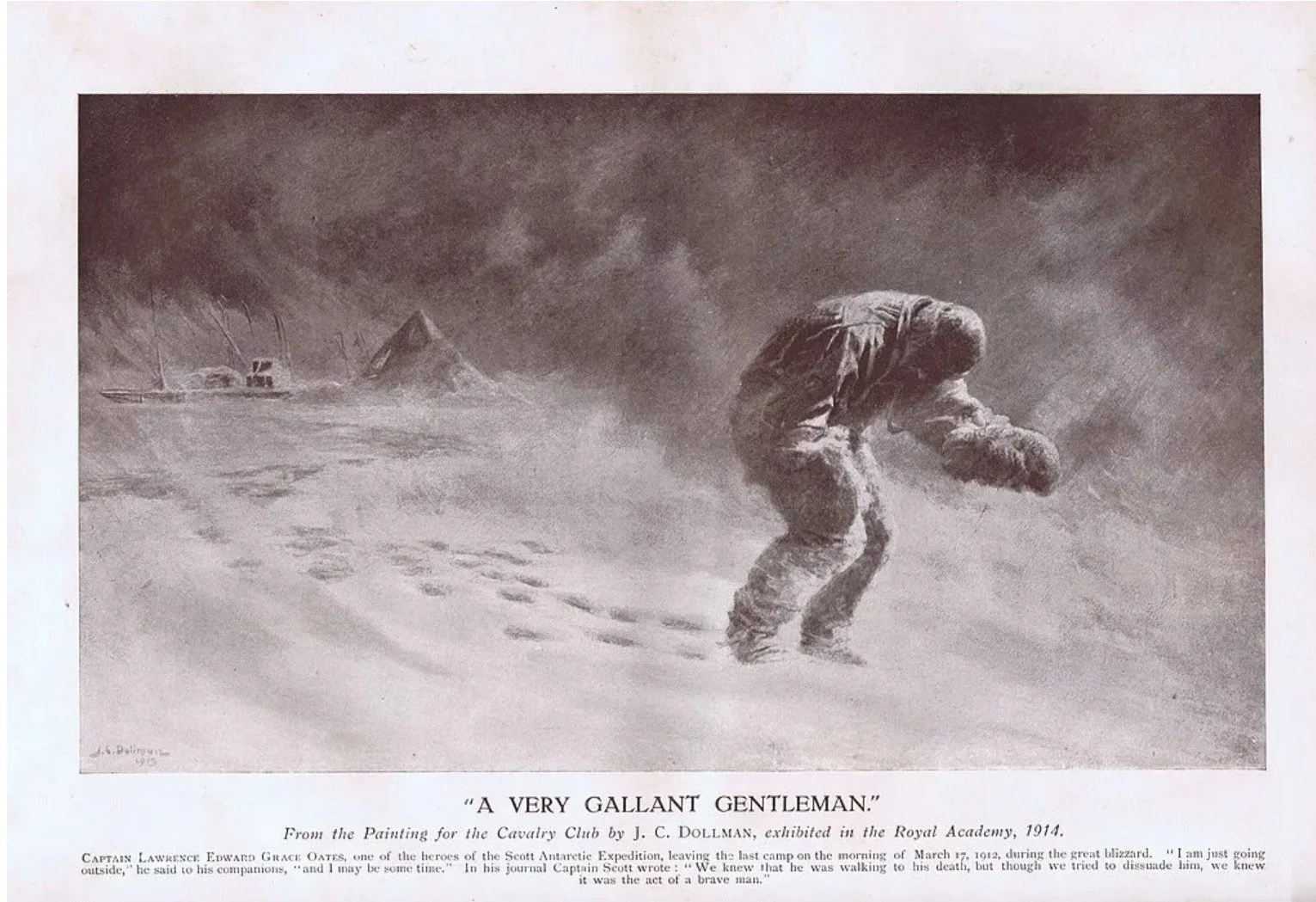

This plate appeared in the 36th The Boy's Own Annual (1913-1914), and is based on the painting A Very Gallant Gentleman by John Charles Dollman. It depicts the last moments of Lawrence Oates. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Starting from Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and sustained by a steady production of works such as Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days (1872) and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Islands (1883), adventure fiction increasingly and literally starts to travel in the heydays of the British empire.

The world begins to be imagined as either places of familiarity or places where familiarity must be extended and exerted.

Perhaps nowhere was the training for this imagined map of the world more urgently ingrained than in the small but influential group of public schools in Britain.

A theme proliferate in Rugby student magazines around this time, for instance, is various kinds of travel writing. Some of these are detailed descriptions of the landscape, people, animal, objects and life in the colonies, while some others relay accounts of “true stories”.

For instance, The Acorn, published between 1890 to 1894, carries articles such as:

“A Visit to Samoa”

“School Life in Australia”

“Life in the Australian Bush”

“Some Curious weapons”

“A Voyage to Shanghai”

“A journey to Australia”

“Our menagerie”

“Correspondences [From Madagascar]”

“Letters From Far Distant Countries” [present day Yantai in Shandong province, China and Melbourne]

“Another Australian Letter”