The equation of slavery to “fagging” is absurd, but the comparison made opens up an interesting connection between the performance of hierarchy within public schools to that enacted within the British Empire. Philip reflects to us a world where the empire becomes an extension of the school grounds and to where colonised peoples replace the “fag” of an officer’s golden years.

Though my school days are becoming a more distant memory, I come back time and time again to one message; “this is preparing you for the real world.” And while I’m yet to construct an electrical circuit or expand a bracket, at the ripe age of 20 I’ve found myself in quiet agreement. In sitting through my weekly lessons on “British Values”, to being told to be practical over passionate, my path to “productive citizenship” was set.

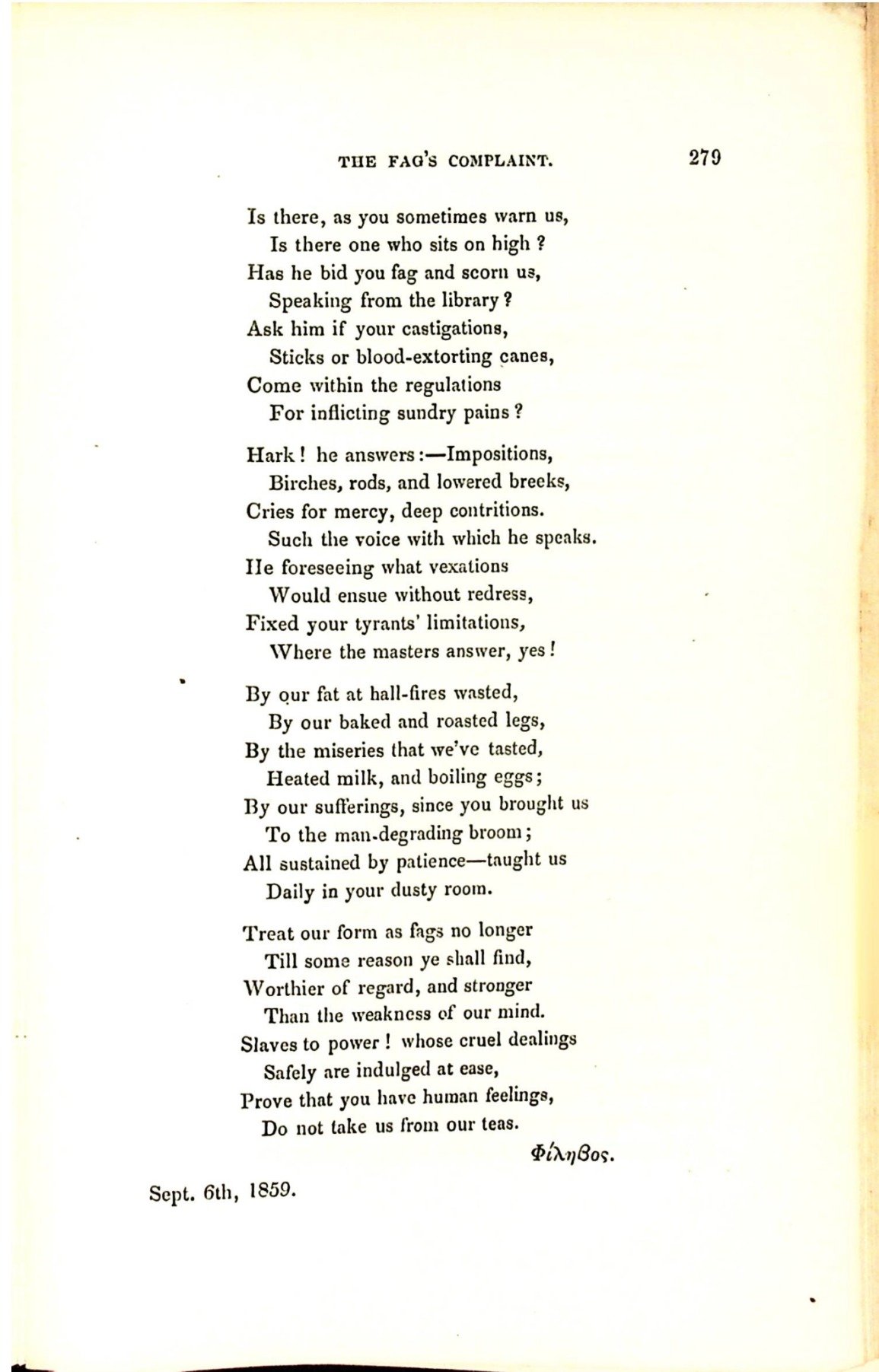

Although I left school in 2020 and not 1850, then, as now, school acted as a microcosm. “Fagging”, far from an indiscretion of adolescent boys, was a test run for the structures and ideologies necessary for those set to rule. The system mirrored the strict organisation of British colonies, organisation which supported four hundred years of dominance. Hierarchy lay at the heart of this. Put simply by the Westminster Review (1835), the system encouraged the division of mankind into two sectors: tyrants and slaves. Mirroring the rise of natural history and scientific racism, this division was predicated on grounds of inborn might and intellect. The poem Man in the Rugby student magazine The New Rugbeian shows the dissemination of this concept in a poetic landscape:

“They met, and in each other’s face/ Gazed with mutual dread: Man stood his ground: the bestial race/ In awe and wonder fled.”

Similar to the physical weakness of the “bestial race”, the “weaker brains” of young boys rendered servitude and punishment appropriate. As lesser beings, exposure to toil and the odd beating would act at best as a lesson, and at worst a deserving punishment. As they aged out of the public school system, these tiers of humanity translated easily towards the nations of empire. But where schoolboys would soon “forfeit” their lowliness through age, those subject to British rule were confined to their inadequacy.

In his book Must England lose India? (which was banned from circulation in India), Arthur Osburn, a soldier in India, describes this phenomenon through his “school-boy superiority complex”. Knowing that cruelty to the “fag” was socially acceptable, demanding compliance from the Indian was a natural step. In a system based upon birth-right and not reason, nonconformity or “cheek” became even slight resistance. Osburn characterises this in an incidence where a servant was almost beaten to death over a favoured cart. Despite exacting life-threatening injuries, “cheek” was justification enough. Osburn wrote:

“Orders, however rash, unreasonable or unjust, or however brusquely or even insolently given, must be obeyed, or the offending one will be treated with insult or with physical violence which a prefect of an English Public School – who is himself little more than a child – may inflict on a somewhat smaller child, may inflict on some third-form boy who dares to question his authority, or whose manner he dislikes, or who is not sufficiently submissive and subservient to satisfy the amoure propre of his lordship the prefect.”

But how did this system remain intact? Suffering the horrors of ill-treatment, why did the majority of boys seek to replicate their experience? A vicious cycle, it is precisely because they suffered that many felt entitled to provoke suffering. The older boy felt he had served his time and was unlikely to relent the established privileges he had fought towards; attempts to rid of “fagging” from public schools met with determined opposition as late as the 1980s.

Many also aggrandized a “hardening effect” tied to contemporary ideals of masculinity. Reiterated from school masters to the Prime Minister himself, boys were encouraged to find pride in cruelty. If this was resisted, it was fought through corporal punishment and social alienation. Though the “blood-extorting canes” of Philip’s piece are perhaps a tad dramatized, punishments with “birches, rods and lowered breeks” were commonplace. Where violence becomes an acceptable response to slights, self-restraint becomes unreasonable and “soft”. Arthur Osburn wrote that:

“After all, we English people do not really learn self-control at school, where we swear even at play; so why should we not swear at an [Indian], and beat him too?”

Eagerness to assimilate continued. When Osburn suggested restraint towards the abuse of “whole families” he was met with immediate hostility: “only by rapidly changing the subject did I avoid falling under the unbearable suspicion of being pro-Indian”. The “fag” who challenges the prefect is beaten; the boy who shows weakness to his peers is bullied. And so, individuality becomes conformity – the” respectable, conventional, conservative fellow”, is soon the “strong and silent” colonial hero.

“Worthier of regard, and stronger”, neither the “fag” nor citizens of empire were to find much peace in a system which saw their exploitation as part of a “greater” purpose: the rise and rise of Britannia.

Sources:

Φίλπβος, “The Fag’s Complaint”, The New Rugbeian, 1:9 (Rugby, 1859), pp. 278–9

“W.”, “Man”, The New Rugbeian, 1:3 (Rugby, 1858), pp. 58-60

Anonymous, “On Fags/ The Model Fag”, The Cresent, 3:1 (Rugby, April 1867), pp. 19-23

Anonymous, “Our Great Serial: Whithersoever”, The Sun, 1:2 (Rugby, January 1914)

Osburn, A., Must England Lose India? The Nemesis of Empire (Somerset, 1930)

Nash, P., “Training an elite: the prefect-fagging system in the English public school”, History of Education Quarterly, 1 (1961), pp. 14–21

Evers, C. R., “Rugby”, The Meteor, 860 (Rugby, November 1939), pp. 131–4