Skye (Rugby School, Year 13)

The debate on repatriation

Rugby School seems to have a close connection to the British punitive expedition to Benin conducted in February 1897. The February 1900 edition of the Meteor, a school publication, tells us that on the 31 January 1900, Captain Boisragon lectured the Rugby boys on ‘The Benin Massacre of 1897’. In January 1897, Boisragon was one of only two survivors of a small British expedition to Benin, which was attacked and defeated, prompting the Benin punitive expedition the following month. His published account of the Benin massacre is one of few such books. While he was not an Old Rugbeian, he was clearly a figure of interest for the School since he came to give a talk to Rugby’s boys.

Another key figure, Captain Herbert Sutherland Walker, was educated at Rugby and went on to be a member of the punitive expedition. There, he looted a number of objects, many of which are now in the British Museum. We do not know the specific number of objects he took, but he photographed and wrote about a variety in his diary. His grandson, Mark Walker, when he came into possession of much of his grandfather’s collection in 2013, considered that they ought to be repatriated, given their importance to the people of Benin City. He returned two Benin bronzes to the Oba, the king, in 2014. In November 2021, two Itsekiri wooden ceremonial paddles brought back by Captain Walker from the 1897 expedition were on loan to the Pitt Rivers Museum, before they return to Nigeria. The idea of repatriation sparks debates among historians and museum curators. Mark Walker suggests that the British Museum could use modern technology to make perfect casts of its whole collection and send it all back and, he said, we wouldn’t know the difference. The question that remains, therefore, is what Rugby should do with objects like those discussed in podcasts featured on the Schools of Empire Project website, a divination bowl and a ceremonial mask respectively, from the Yoruba people.

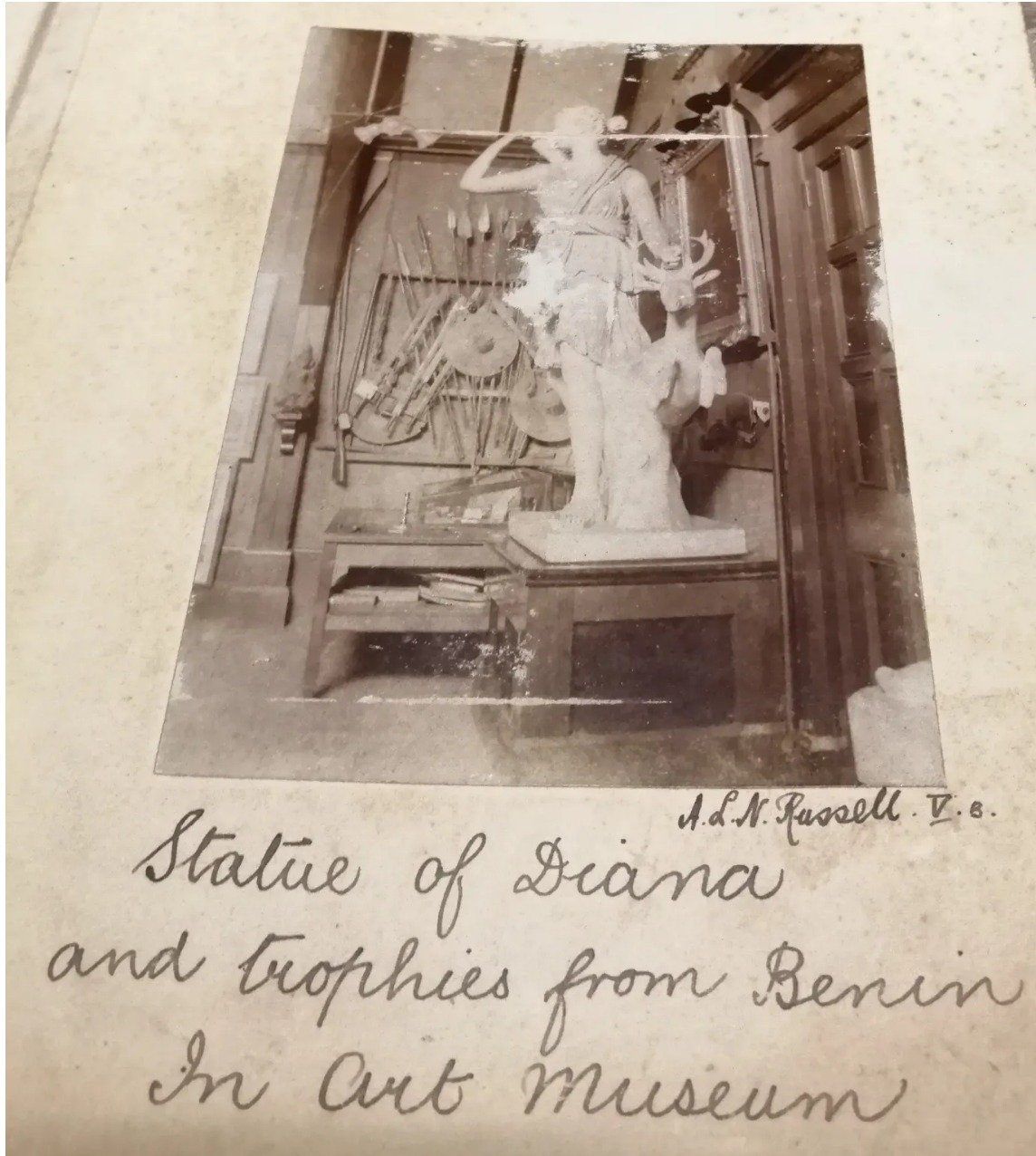

Photograph from the "1902 album" in Rugby School Archive with the label "Statue of Diana and trophies from Benin In Art Museum". The Art Museum was housed on the first floor of the Temple Reading Room. Rugby School is no longer in possession of these artefacts; no information about the break-up of the collection or their current whereabouts is preserved.

Restitution is giving back something lost or stolen to its original owner. As discussions around these issues have grown in recent years and have even begun appearing in popular culture such as the opening scenes of Hollywood blockbuster Black Panther, we have heard many emerging voices of individuals, organisations, and governments. While such debates date back at least to the mid-twentieth century, modern movements like Rhodes Must Fall and Black Lives Matter have brought the conversations to greater prominence. Some institutions have already begun the process of returning some artefacts to the countries from which they were taken. One key example of this is in Germany. In July 2022, the German government reached an agreement with the Nigerian government to return permanently 1,100 Benin Bronzes that they had in museums (Harris, 2022). However, such agreements remain uncommon. Many are yet to release statements about their position on restitution. This is still uncharted territory, and the debates will perhaps reach no conclusion soon.

Head of a king oba, Nigeria, Benin kingdom; brass; 19th century; Ethnological Museum, Berlin. Image credit: Wikipedia.

According to a report from 2018, France alone has around 90,000 African artworks. The British Museum houses more than 8 million artefacts in total, with only 1% on display at any time. A significant proportion of these were taken from their original contexts during looting and collecting under the British Empire. The British Museum is the ‘world’s largest receiver of stolen loot’, according to Geoffrey Robertson KC (The Guardian, 2019). These debates, therefore, are of importance to all those who have ever visited museums in almost any European country. Under a 1963 Act of Parliament the British Museum is not allowed to give objects or return ownership to other institutions permanently. In 2010, an Amendment to the Act was brought before the House of Commons. It wanted to make exceptions for objects where they would be better enjoyed elsewhere or had a provenance which indicated a need for them to be returned. It reached the second reading in the Commons but went no further.

Benin Bronzes; British Museum. Image credit: Wikipedia.