Excy Hansda (University of Liverpool)

The life (and accidental death) of a revolutionary educator: George Cotton, bishop of Calcutta

Introduction

George Edward Lynch Cotton was born in Chester on 29 October 1813. His father was Captain Thomas Davenant Cotton of the 7th Fusiliers, who tragically died in the battle of the Nivelle just a fortnight after his son’s birth. Cotton’s grandfather was George Cotton, the dean of Chester, who had passed away in 1805. George Edward Lynch Cotton received his education at Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge, where, in 1836, he earned a first-class degree in the classical tripos.

Portrait of George Cotton. Image credit: Wikimedia.

Shortly after his graduation, in 1837, Dr Thomas Arnold, an esteemed educator and historian, appointed Cotton as an assistant master in charge of a boarding house at Rugby School. As a teacher at Rugby, he became known as the young master of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, a novel published in 1857 by Thomas Hughes, which was set at Rugby School. Cotton spent fifteen years at Rugby, gradually gaining a reputation as an efficient master dedicated to the moral and intellectual training of his pupils.

In 1845, Cotton married his cousin, Sophia Anne Tomkinson of Reaseheath in Cheshire. They had two surviving children, a son and a daughter.

In 1852, Cotton became the headmaster of Marlborough College, where he implemented many educational reforms and introduced new pedagogical methods, setting a new culture there which also influenced other public schools. In 1858, Cotton left for India to become the bishop of Calcutta, where he played a significant role in developing educational policies and infrastructure, as well as missionary practices.

Life in Rugby and Marlborough

After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts at Cambridge in 1836, Cotton became an assistant master at Rugby School. In 1840, he became the master of the fifth form. Thomas Arnold, the headmaster of Rugby School from 1828 to 1841, had a huge influence on Cotton’s life. Following the principles and spirit of Arnold, Cotton brought about substantial change at Rugby and later at Marlborough, turning “truly a barbarian school into a place where the Philistine virtues predominated” (Mutimer, 1971). Arnold’s influence on Cotton can be noted in several sources. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Cotton “thoroughly absorbed and reproduced in his own life and work the most distinctive features of Arnold’s character and principles” (ODNB). Cotton’s memoir, edited by his wife, Sophia, notes that “The influences of this appointment on his afterlife were incalculable. First among these must be counted the impression produced upon him by the character and teaching of his great chief. It is not too much to say that there was none of all the direct pupils of Dr Arnold on whom so exclusive a mark of their master’s mind.” (Cotton, 1872)

Old Quad, Rugby School. Image credit: Wikimedia.

Cotton’s time at Rugby witnessed slow but gradual developments in his personal and professional lives. Despite the strains that accompanied his responsibilities as a school master, he maintained a boyish sense of humor that helped him persevere. However, beneath this humor was an intense religious life that guided his daily actions. It was during his time in Rugby that he found his true purpose in life: to deepen the Christian side of public school life.

Thomas Arnold. Image credit: Wikimedia.

As a clergyman and educator, he took his pastoral duties towards his pupils seriously. He published devotional manuals for schoolboys, which were widely used in schools throughout England and the empire. Additionally, he regularly delivered Sunday evening sermons, laying the foundation for his future success as a preacher. He preached at various places, including before the University of Cambridge in 1843.

Cotton also regularly interacted with his pupils, taking the time to understand their thoughts and feelings in order to prepare them for confirmation. It was through these conversations, both inside and outside the classroom, that he carefully studied the details of education, which would later inspire his reforms. Along with Thomas Arnold, Cotton “showed astonishing patience and forbearance with [the] incorrigibly idle pupil [Tom Hughes]” (Mack and Armytage, 1952, p. 21). This anecdote demonstrates the kind of dedication he devoted to students’ learning. As his memoir mentions, he did not see himself as a teacher of boys but of men (Cotton, 1872, p. 14).

In 1852, having previously failed to be appointed headmaster of Rugby on the retirement of A. C. Tait, Cotton was appointed master of Marlborough College, which, though established only nine years earlier, was in need of reform. Cotton – along with his friend C. J. Vaughan, headmaster of Harrow – is credited with introducing organized games to English public schools. When Cotton was the headmaster of Marlborough, the first offences he clamped down on were breaking bounds and drinking. Before his arrival, Marlborough College did not have a strong tradition of games. It was Cotton who introduced rugby and cricket in his effort to encourage rule-abiding behaviours. He noted that games provided an increasing attraction to the detriment of poaching and drinking (Mutimer, 1971).

Marlborough College. Image credit: Wikimedia.

Cotton is also noted for his “Red Book”, a notebook kept in the staff room which Cotton and other staff member used to note details of school life and rules. The idea of putting rules down in writing is symptomatic of the principles of ordered life that Arnold gave to Cotton, and which, in turn, Cotton exported to Marlborough and maybe India. Written rules and regulations were at the forefront of Cotton’s attempts to reduce the “barbarian” element in the school (Mutimer, 1971).

Cotton also brought to Marlborough the Rugby style of the prefectorial system, which initially met with resistance from Marlborough staff. The Red Book records the duties of the prefects, the responsibilities they had, and their right to punish juniors. Every fortnight they were supposed to meet for “Court” meetings relating to various aspects of their duties. Sometimes, Cotton used to send subjects for discussion at “Court”. At the end of six years, Cotton left Marlborough with a high reputation among public schools.

Emphasis on Christian learning

Christian teachings in schools were important to Cotton. Often, he used to refer to the public school as the “Temple of God” (Cotton, 1854, p. 2). Many of his sermons exhorted students not to be thoughtless or careless. In one of his sermons, he said:

“At a public school, too, they [students] are exposed from their very close contact with their companions to the influences of bad example and bad society, in a greater degree than they will be afterwards when they live more independently and alone. But then the temptations which a boy feels to be thoughtless and disobedient, or to swear, or deceive his masters, or to neglect his appointed work, are in no way greater than the snares which are placed in the path of a grown-up man by selfishness, and worldliness, and ambition. It is hard to see why such sins as these are at all less odious to God, or less likely to be fatal to our salvation, than carelessness and disobedience. Both classes of sins are the peculiar faults of different ages, both are to be resisted by the same means; both can be conquered by the same almighty help of God the Holy Ghost; both will be conquered, if those who are under their influence pray earnestly for His aid, through Christ their Saviour; and both, if persisted in, must lead to eternal death” (Cotton, 1854, p. 4).

One can identify here the emphasis on living a Christian and disciplined life, starting at a very young age. He laid special emphasis on prayers: “Prayer is a constant source of invigoration to self-discipline: not the thoughtless praying, which is a thing of custom, but that which is sincere, intense, watchful. Let a man ask himself whether he really would have the thing he prays for; let him think when he is praying for a spirit of forgiveness, whether even at this moment he is disposed to give up the luxury of anger” (Cotton, 1854, p. 4).

For the boys, he designed the timetable so that a substantial amount of time was dedicated to prayers. In his book Short Prayers and other help to Devotion: For Boys of a Public School (1854), he meticulously noted prayers and subjects for a comprehensive list of different occasions, such as: school prayers; prayers for a deeper sense of Christian duty; prayers after some particular and grievous sin; before and after receiving communion; for candidates for confirmation; in time of sickness; thanksgiving for recovery; in times of affliction; after a death in the school; at times of prosperity; at the prospect of an examination; on birthdays; and prayers to be said before, during, and after the holidays. He laid special emphasis on prayers for self-examination, which he formalized. Cotton understood that it would be difficult for boys to give up much time for prayers, therefore he recommended short periods in every day solely dedicated to prayers.

Life in Calcutta

Cotton’s resignation from Marlborough was caused by his appointment as the sixth bishop of Calcutta in 1858, which was made on the recommendation of A. C. Tait, whose colleague he had been at Rugby. Though he had no special knowledge of India, he enjoyed a good reputation as a moderate ecclesiastic, and it was difficult to find candidates for the post, since many British nationals were reluctant to go to India so soon after the beginning of the First War of Indian Independence. Compounding this, the events of 1857 also led the British Crown to limit missionary work and Christian education in schools in India.

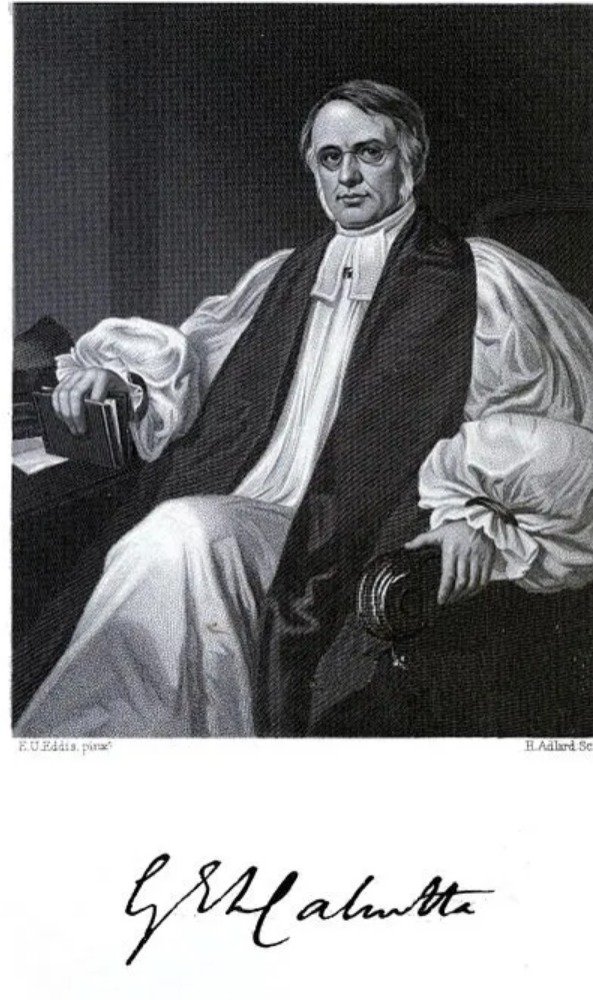

George Cotton as bishop of Calcutta. Image credit: Wikimedia.

In India, Cotton supervised the dioceses of Madras (mod. Chennai) and Bombay (mod. Mumbai), as well as Calcutta (mod. Kalkota). He exercised direct supervision over the Anglican chaplains who served the British troops and European congregations in India. Cotton maintained contact with the scattered chaplaincy through regular pastoral letters and extensive visits. As bishop, he was called on frequently to negotiate with the Church of England missionary societies and settle disputes. But what Cotton is particularly known for is the establishment of schools for the Indian and European populations. Many of these were Europeans who could not afford to send their children back to England for their education. At the time, it was not thought appropriate for Europeans to attend schools with Indians, and mixed-race people were discriminated against by both Indians and Europeans. Cotton believed that education was crucial for them. The very thought that future generations of English settlers might grow up with no Christian education was a source of great anxiety for him. He believed that a generation of non-Christian Englishmen springing up among the population would inhibit the spread of Christianity. With the rise of Western education in India, it was imperative that educational facilities be provided for these students. In his memoirs, Cotton recalled that “he hoped that a sound physical, intellectual, and religious education might, under God’s blessing, not only benefit children likely to remain permanently in the land but might also, indirectly, tend to remove the barriers of prejudice and misunderstanding which separate the races to whom India is now a common country” (Cotton, 1872, p. 14).

In 1860, Cotton came up with a comprehensive plan and Governor-General Canning accepted the idea and set forth a programme later in the year. As per Cotton’s memoir, the plan would lead to: (1.) the establishment of a system of education, physically and intellectually vigorous, suited to the requirements of commercial life, the army, or of Calcutta University, with religious teaching in conformity with the Church of England, modified by a conscience clause for dissenters; (2.) the foundation of schools in the hills of the Himalayas, followed by plans to make similar schools in the plains for the lower classes; (3.) endowment funds to impart permanence and stability to new institutions (Cotton, 1872).

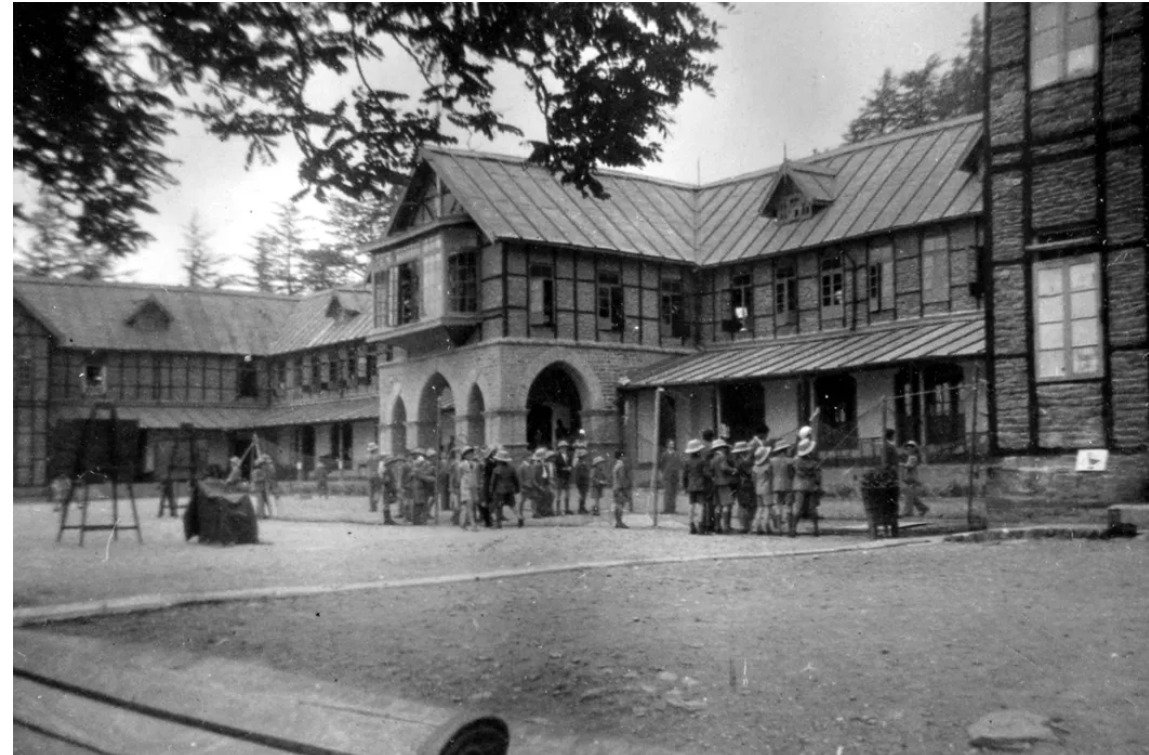

Bishop Cotton School Shimla in 1944. Image credit: Wikimedia.

According to the plan, boarding schools would be set up in the Himalayan hills, which had a climate close to that of Europe and which were relatively isolated from poorer communities. The boarding schools appropriated the model of an English public school, providing religious teaching in conformity with the Church of England (with modifications for people of different faiths), as well as practical knowledge and other learnings. The day schools were designed to impart practical education considered suitable for the sons of European skilled workers who worked on engineering projects for railways, roads and other infrastructure. During Cotton’s episcopate, boarding schools were established in Shimla, Darjeeling, and Mussoorie. Later, other boarding schools were established in Nainital, and Dalhousie. Only later were day schools in the plains established in Bengaluru and in Bhopal. Many of these schools were named after Cotton as monuments to this part of his work.

2009 Stamp of India - Bishop Cotton School Shimla. Image credit: Wikimedia.

On 6 October 1866, Cotton’s died in an accident when his foot slipped on a platform of rough planks when he was crossing the River Gorai to board a steamer. He fell into the river and was carried away by the strong undercurrent, never to be seen again. He left behind him a significant legacy as a pioneering colonial educator. There is no evidence for the apocryphal tale that he was eaten by a crocodile.

References:

Cotton, George Edward Lynch, Sermons (1867); <https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.218299/page/n103/mode/2up>.

“Cotton, George Edward Lynch (1813–1866), Bishop of Calcutta”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed 16 April 2023; <https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-6412;jsessionid=B0DA7192BE43F2EE3577AF0A4DFA0740>.

Cotton, George Edward Lynch, Short Prayers and Other Helps to Devotion: For Boys of a Public School: George Edward Lynch Cotton (1854); <https://archive.org/details/shortprayersand00cottgoog/page/n30/mode/2up>.

Cotton, Sophia, ed., Memoir of George Edward Lynch Cotton, D.D., Bishop of Calcutta, and Metropolitan (1872); <https://archive.org/details/memoirgeorgeedw00cottgoog/page/n36/mode/2up>.

Mack, Edward C., and W. H. G. Armytage, Thomas Hughes: The Life of the Author of Tom Brown’s Schooldays(1952).

Hughes, Thomas, Tom Brown’s Schooldays, 3rd edn (1857).

Mutimer, Brian T. P., “Arnold and Organized Games in the English Public Schools of the Nineteenth Century” (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Alberta, 1971).